The world now faces multiple problems, and a new policy approach is required. The priorities are to achieve better environmental outcomes, and better outcomes for people – especially those facing deprivation and/or precariousness. This proposal focuses on the human component, and specifically on the contribution that the economy can make. It suggests a criterion of success for the economy, and a monitoring system that corresponds to it.

This would be complementary to GDP: it is a proposal for “GDP and beyond”, not “beyond GDP”. As a measure of the size of the marketed output of an economy, GDP is indispensable for economic management. However, since it was developed many decades ago, there has been dissatisfaction with its use as a measure of economic wellbeing.

An additional element is therefore needed that is complementary to GDP, also with a focus on the economy, that evaluates its degree of success. This new element would need to be free from the three main traditional criticisms of GDP when (mis)used as a measure of economic success:

- that it counts harmful products/activities as well as good ones;

- that it neglects inequalities;

- that it ignores unpaid labour such as housework.

The task is to develop a measure, and a monitoring system, that corresponds to “success” for the economy. The scope of “the economy” would need to match the SNA definition, together with unpaid labour because it is substitutable with paid labour, and because its omission is a standard criticism of GDP. This implies the need to ask, and to answer, the question “what is it about the economy that is valuable?”. This necessitates a value system that is made explicit, and that commands widespread support.

The prime candidate is the value system embodied in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The aim is that, as far as possible, everyone’s basic needs should be met – a commitment to leave no one behind. The same view underlies other international agreements, and survey evidence finds widespread, although not universal, support for this view.

It can thus be regarded as a shared value system that is widely prevalent across diverse cultures and political beliefs. The foundation is respect for the dignity of all, which in turn promotes inclusion and social justice, and facilitates agency and aspiration. It aims at the minimal acceptable degree of economic wellbeing, in a concrete and readily understandable form. This can provide a narrative – a strong, clear message that is intuitive to communicate, and that can inform public discussion as well as policy development across society. It could be summarised as support for a responsible economy – responsibility for others, and for the environment.

This implies a criterion for the new measure of success of the economy: it should monitor outcomes of economic activity that satisfy basic needs – such items as livelihoods and homes of decent quality and security, a nurturing and educative environment for children, and access to appropriate types of care. Meeting them would minimise distress, promote good health and positive psychological/social functioning, and encourage aspiration and social participation.

There is broad agreement on what items qualify as basic needs. Similar lists of life’s essentials are widespread across different disciplines, including political economy, philosophy, economics, social policy and public health. The contributions encompass a wide variety of ideological viewpoints. In economics, the distinction between needs and wants can be traced back through the founders of the neoclassical school to Adam Smith’s “necessaries”.

The monitoring system would thus comprise the outcomes of economic activity that are relevant to people’s basic needs. These economic outcomes arise from economic outputs, of both the private and public sectors, which include housing, transport, food, education, care, communications and work/livelihoods/income. They correspond respectively to ends and means.

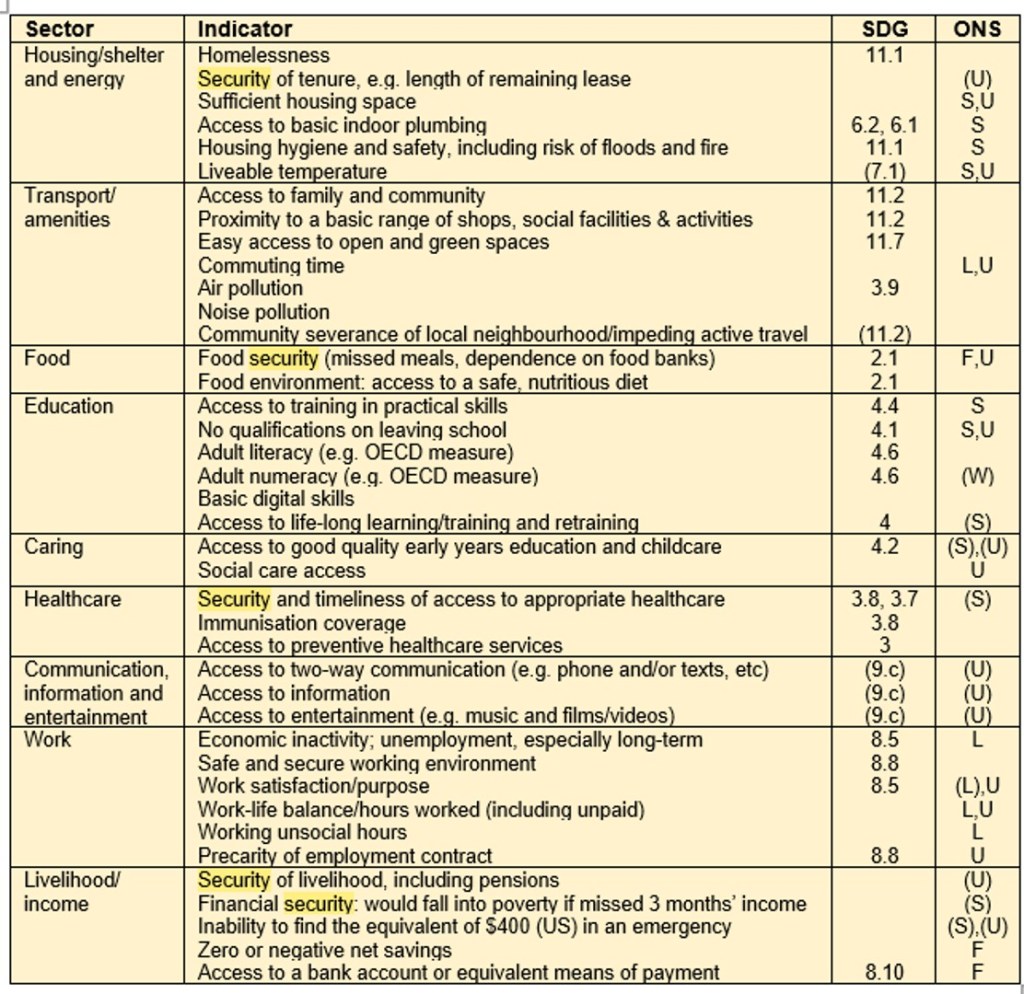

Monitoring economic outcomes of this kind would provide an objective, an incentive and a criterion of success for policy development relating to the economy. This would represent a shift to emphasizing ends – the meeting of basic needs – rather than means, the quantity of economic output (GDP). A provisional list of possible indicators is presented in the table, as a basis for discussion. The choice of items is based on the literature on human needs. It is also informed by the literature on the social and economic determinants of health and the emerging evidence on the economic determinants of subjective wellbeing, because of the strong impact of unmet need on health and wellbeing. Data would be obtained from a combination of surveys, administrative data and other methods. The table also indicates the correspondence of these suggested items with the SDG targets, and with already-existing UK survey data.

Suggested outcome indicators

The column “SDG” indicates the equivalent SDG target; the column “ONS” indicates which UK surveys contain a measure of this item. Brackets indicate imperfect correspondence with the proposed outcome measure.

The UK surveys are: Survey on Living Conditions (S); Family Resources Survey (F); Labour Force Survey (L); Wealth & Assets Survey (W); Understanding Society (U)

This list is intended as a practical step towards the development of a new monitoring system that treats the meeting of basic needs as a priority. It is intended to contribute to work on the monitoring system for the SDGs.

Monitoring these economic outcomes is straightforward. A large proportion of the proposed measures are already available, and many have been used in practice. They are acceptable to the public, and affordable. Only a little development work would be required to create the proposed monitoring system. It is strongly desirable that it should be standardized internationally, albeit with variations to allow for differing levels of economic prosperity.

As an example, in the UK, currently-existing surveys cover a large proportion of the suggested items (listed in the table). The situation is similar in many other UN Member States, and important additional contributions have been made by international organizations such as the OECD.

In some cases, the presently available information from survey data is sparse. For example, existing questions on unmet need for healthcare typically cover medical and dental care, but not others such as mental healthcare and midwifery. In addition, the quality of treatment and its timeliness are not available from this source. Similarly, the quality of childcare is not routinely covered by survey data.

Much of this additional needed information can be obtained from non-survey sources, including administrative data on service usage, outcomes, etc. Other possible sources include “big” data, as well as reports by think-tanks and other organizations, and academic research.

The particular metric that corresponds to the value system to leave no one behind is what may be called the proportion unfulfilled: the proportion of the population who lack some facility, or who do not reach some threshold. Many relevant variables are already in this format, as with the unemployment rate, whereas others would need a threshold to be set, as with overcrowded housing.

The use of the proportion unfulfilled highlights inequalities, at least at the lower end of the income scale, implying that there is no need for a separate measure of inequalities as there is with per capita GDP (and with most other measures). It is compatible with different degrees of inequality higher up the scale, and therefore with a range of political views, implying that it can command wide popular support. An important methodological implication of the proportion unfulfilled metric is that it requires representation of the whole population, including “hard-to-reach” groups.

The information from this monitoring system would be presented as a dashboard in a standardized format, providing informative material for public debate and a practical agenda for remedial action. In addition, the items would be aggregated to create an Index of Economic Outcomes (the IEO), for the overall evaluation of economic success. This would replace GDP as a measure of economic success, retaining it for use in economic management.

In principle, the inclusion criterion and the weights for constructing the aggregate IEO would be based on estimates of the size of the causal contribution of each candidate item to health and subjective wellbeing. Ideally, these would be derived from a comprehensive evidence base, calculated using the population attributable fraction, a standard epidemiological measure. This requires a value for the causal relative risk of each variable, adjusted for the effects of the others. However, a sufficiently robust evidence base is not yet available; initially, reliance will need to be placed on expert opinion.

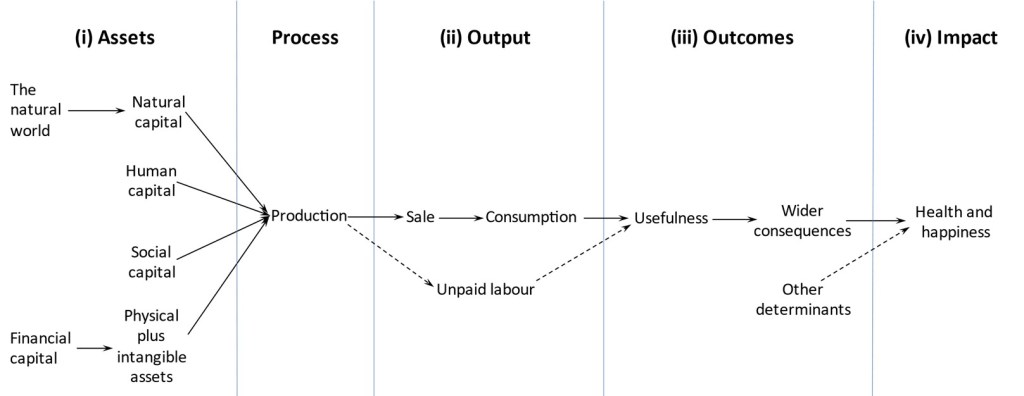

The proposed IEO would fit well within the overall monitoring system for the economy. It would be complementary to valuation of the various types of assets, including environmental monitoring, SEEA and the Inclusive Wealth Index; to economic output including GDP but also unpaid labour in terms of time allocation; and to the human impact, i.e. happiness and health. The relationship between these domains and the production process is shown in the figure; complementary monitoring systems are also required for non-economic topics such as demographic data, and for governance, trust, and personal security (e.g. feeling safe when walking alone at night).

The sequence of assets, process, output, outcomes and impact

(Dashed arrows represent processes that are not part of the System of National Accounts)

This collection of separate, complementary, monitoring systems has a decisive advantage over the type of composite measure that is often proposed in the Beyond GDP literature. It enables the trade-offs and synergies between the different domains to be examined. In particular, combining the IEO with other measures would provide valuable information. Dividing the IEO by the ecological footprint and/or specifically by the carbon footprint would generate a sustainability ratio, the environmental cost of meeting basic human needs. This could be regarded as a measure of sustainable development.

There is now considerable interest in the idea of a “wellbeing economy”, and monitoring of subjective wellbeing is well established. However, monitoring of its economic determinants is more informative – it tells us not just “how well we are doing”, but also “what we need to change to do better” – providing a guide to action. More formally, monitoring intermediate outcomes (in this case, economic outcomes between economic outputs and the impact on wellbeing, as in the figure) has useful measurement properties: they apply to the whole population, they directly indicate where intervention is necessary, and they are present early thus allowing preventive measures to be undertaken, thereby helping to set the policy agenda. This perspective accords with the OECD/EU “Economy of Wellbeing” initiative.

Our Common Agenda, the UN Secretary-General’s vision for the future of global cooperation, asked for a measure of “economic prosperity and progress”. The IEO sets out to measure economic wellbeing as it affects humans, especially those with fewer resources. Thus, it could contribute to meeting SDG17, Target 19: “to develop measurements of progress on sustainable development that complement gross domestic product”.

References

Joffe, Michael. 2024. Evaluating Economic Success: Happiness, Health, and Basic Human Needs. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. Open access, available free of charge at https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-57671-3.

United Nations. 2021. Our Common Agenda – Report of the Secretary-General. New York: United Nations.